Like, Comment, Discriminate: Racist Discourse on Dutch Instagram

The Sharing Perspectives Foundation and Build Up believe the answer lies in dialogue. By engaging in open and honest conversations and by posting alternative, unifying narratives, we can foster empathy and understanding while dismantling harmful beliefs and stereotypes. This theory forms the foundation on which we build The Digital Us: an online training program designed to empower young people to intervene in racist discourse on social media.

The Digital Us brings together people who have experienced racism online with those who have not. It offers young people a safe online space to engage in conversations around topics such as ethnicity, representation and privilege. Together, they learn how to best go about intervening in racist debates. Bystanders become upstanders, and the burden of addressing online racism is no longer solely on the shoulders of its victims.

This week is an exciting week for The Digital Us as the first group of participants will embark on their learning journey. To be able to guide them not only on how to intervene but also on where to intervene, we carried out a social media analysis. The findings of this research, which focused on Dutch Instagram, unequivocally reaffirms the relevance and importance of The Digital Us, with nearly 4% of the 309,083 comments in our dataset found to be likely racist.

The social media analysis also provides us with valuable insights, including:

– National news media attract the largest number of racist comments;

– News reports about crime are the most common and also attract the most racist comments;

– A disproportionate number of racist comments are posted under messages about Islam;

– Each type of racist commentary follows specific discursive patterns.

For more findings, check out the full report.

Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange as a new form of education

As one of my case studies, I focused on the Virtual Exchange format of the Sharing Perspectives Foundation as I noticed they were aiming to do something different with their online courses. I talked to staff members about the design of the format and studied the daily operation of the courses. I tried to understand what is specific to the SPF format and consider the educational implications of these specificities. In the end, the purpose of my study was to give a more detailed view on the way open online education initiatives could work, and formulate some more grounded claims about their role in the educational field.

What I found is that, in many respects, the Virtual Exchange format of the Sharing Perspectives Foundation does something totally different than traditional education. Digital technologies are implemented in such a way that young people from all over the globe share resources about complex issues that play at a global level, like the videos and reading materials. Next to that, the Virtual Exchange format integrates discussions about local effects of these global issues, by encouraging participants to describe their personal experiences, to give local examples, and to share interviews with their friends or family members about the discussed topics. These activities in the Virtual Exchange give a stage to differences between participants who are from various geographical regions and have different backgrounds. But they may also cast light on surprising similarities: participants from different parts of the world may share passions, aspirations, experiences, or even linguistic expressions. What the Virtual Exchange format introduces, in this way, is a continuous connection between the local and the global, online and offline, personal and common, or differences and similarities.

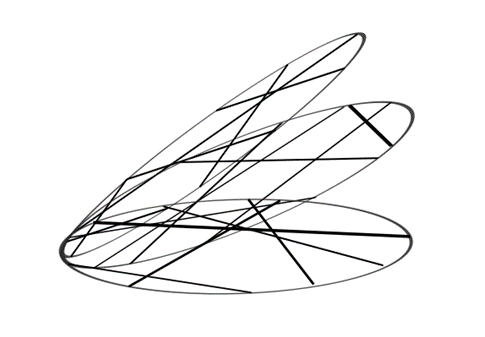

The image visualizes how differences and similarities unfold during the dialogue sessions, like a ‘color wheel’ or a fan. That is, on the one hand, this unfolding shows dissimilarities (in the image, the different lines making up the circles. On the other hand, these differences are held together through commonalities (in the image, the ‘joint’ or hinge keeping the different circles together). Image retrieved from: van de Oudeweetering, K., & Decuypere, M. (2020). In between hyperboles: forms and formations in Open Education. Learning, Media and Technology, 1-18 (Advance online publication). doi: 10.1080/17439884.2020.1809451

As much as digital technologies establish these new connections, they are not without glitches. Poor internet connections, hardware issues, or overburdened servers frequently interrupt the dialogue sessions, and sometimes prevent participants from entering the dialogue sessions. I experienced this myself one time when there was a power cut in my street and my apartment. Luckily, there is a technical team offering support in these cases and facilitators try to integrate these technical problems in the dialogue session: they encourage participants to think about the fragility of digital connections, and how the ability to connect online often heavily depends on local contexts.

Besides these specific characteristics of the Virtual Exchange format of SPF, I also noticed that the online design bears similarities with ‘traditional’ school settings. For example, the small dialogue groups give the same safety as a class, the online meeting rooms are designed to create a similar feeling of commonality as in a classroom, and there is a course outline that structures the learning materials like a regular curriculum. In this sense, the Virtual Exchange format of SPF integrates various characteristics of education that we are familiar to. Moreover, it is this continuity that makes the format work: we need closedness to build bonds, we need some sort of place and time to come together, and we need a timeline to commit to a learning trajectory. Therefore, this study helped to see that the format does not introduce a radical disruption from or for traditional forms of education, but establishes new dimensions and connections to existing, formal education settings.

The study is accessible via https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17439884.2020.1809451, but subscriptions or university networks are required.

About the author

Karmijn van de Oudeweetering is a 29-year old PhD student at the KU Leuven in Belgium. Her research is focused on open online education initiatives, how they are embedded in European education policy, and how they are consequently realized. Furthermore, the research focuses on describing and visualizing forms of space and time that come into being through these online educational developments.

Virtual Exchange or Virtual training?

Methodological principles

Virtual exchange |

Virtual training |

|

Designed around |

process | content |

Learning is |

implicit | explicit |

Learner is |

leading in process | central in design |

Method of instruction |

facilitated | instructed |

Interaction between learners |

is the core of the learning | is supportive to the learning |

Emphasis on |

Contemporary themes | Timeless themes and skills |

Interaction is |

mostly synchronous | synchronous & asynchronous |

Connection is made to |

people | content |

Assignments |

deepen the learning process | check the learning process |

Learning outcomes are |

flexible to each participant | identical for each participant |

A virtual exchange

A designed interactive process in which the learner is leading. Learners interact synchronously under the guidance of facilitators to engage on contemporary themes. Through the interactive process learners implicitly develop various skills. However, to which extent they develop those skills is flexible and dependent on their own needs and previous experiences. Participant’s curiosity might be triggered and stimulated, their self-esteem can be enhanced, their previously held beliefs and viewpoints may be challenged and their listening skills might improve. The assignments learners engage in are solely designed to deepen the learning process. Submitting assignments is sufficient to pass the course as meta-analysis on learning outcomes for all participants together show us that the overall learning outcomes are being met at a certain level of participation and assignments submission.

A virtual training

Is designed around specific content or skills. Learning outcomes are explicit and equal to all participants. Learners are instructed, and engage in the training through readings and video-materials and interact with peers or instructors both synchronous and asynchronous to support their comprehension of the content. Assignments are used to control for this comprehension and can be failed after submission. Trained skills and taught content are timeless and do not necessarily have a link to contemporary issues.

Learning objectives

Typically, through virtual exchanges learners develop what is referred to in literature as soft skills, transversal skills or 21st Century skills. Such skills include curiosity, self-esteem, tolerance to ambiguity, serenity, resilience, critical thinking, listening skills, or cross-cultural competences. Through virtual trainings, participants typically develop more concrete or ‘hard’ skills, like digital competences, foreign language skills or media-literacy. This also clarifies the difference in learning outcome measurement. It is at least unethical but arguably impossible, to fail a participant on a low level of self-esteem or by not being curious enough. It is possible to measure someone’s ability to use online tools, such as Google sheets or to measure a certain language proficiency or the ability to distinguish between real and fake news. The above is not exclusive, but illustrative to a typical learning outcome for each model.